Welcome to the ODX Inflammation Series. In this series of posts, the ODX Research team dives into the topic of inflammation with an exploration of inflammatory cytokines and their role in the assessment and treatment of inflammation.

Inflammation The Fire Inside: Overview

Dicken Weatherby, N.D. and Beth Ellen DiLuglio, MS, RDN, LDN

The ODX Inflammation Series

- Inflammation Part 1 - The Fire Inside - Overview

- Inflammation Part 2 - The Fire Inside - "Inflammaging"

- Inflammation Part 3 - A Focus on Cytokines

- Inflammation Part 4 - Cytokines & Their Functions

- Inflammation Part 5 - The Cytokine Storm

- Inflammation Part 6 - Cytokine Biomarkers

- Inflammation Part 7 - Establishing Cytokine Ranges

- Inflammation Part 8 - Interleukin 6

- Inflammation Part 9 - Interleukin 10

- Inflammation Part 10 - The IL-6 : IL-10 Ratio

- Inflammation Part 11 - Resolution & Intervention

Inflammation refers to signs, symptoms, and cellular actions that occur in a complex response to infection, injury, trauma, overuse, toxins, or radiation exposure. Technically inflammation is a is a defense mechanism.[1]

By definition:

“Inflammation is the complex biological response of vascular tissue to harmful stimuli such as pathogens, damaged cells, or irritants that consists of both vascular and cellular responses. Inflammation is a protective attempt by the organism to remove the injurious stimuli and initiate the healing process and to restore both structure and function. Inflammation may be local or systemic. It may be acute or chronic.” [2]

Signs and symptoms may include swelling, edema, redness, warmth, pain, stiffness, immobility, oxidative stress, tissue damage, and loss of function.

Associated diseases include those that end in “-itis” (e.g., arthritis, hepatitis, gastritis, etc.) as well as chronic diseases such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, obesity, and cancer. Inflammation is important in the early stages of wound healing and immune response to infection. However, prolonged, chronic inflammation can be detrimental.[3] Chronic inflammation may not be as symptomatic or obvious as acute inflammation that occurs in response to an injury or infection.

Both infectious and non-infectious factors can trigger inflammation, stimulating inflammatory cells such as adipocytes and macrophages to produce pro-inflammatory cytokines. Once an inflammatory cascade is activated, its prolongation may cause damage and subsequent disease in various tissues including the brain, heart, intestinal tract, kidney, liver, lung, pancreas, and/or reproductive system.[4]

Research suggests that impaired autophagy, the lysosomal degradation and clearing of cellular debris, denatured proteins, damaged organelles, and pathogens can contribute to chronic inflammation.[5] [6]

Etiology of Inflammation

Non-infectious factors |

Infectious factors |

|

|

Inflammatory Cascade

The inflammatory response involves a highly coordinated network of many cell types. Activated macrophages, monocytes, and other cells mediate local responses to tissue damage and infection.

At sites of tissue injury, damaged epithelial and endothelial cells release factors that trigger the inflammatory cascade, along with chemokines and growth factors, which attract neutrophils and monocytes.

Inflammatory Mediators

The first cells attracted to a site of injury are neutrophils, followed by monocytes, lymphocytes (natural killer cells [NK cells], T cells, and B cells), and mast cells.

Monocytes can differentiate into macrophages and dendritic cells and are recruited via chemotaxis into damaged tissues.

Inflammation-mediated immune cell alterations are associated with many diseases, including asthma, cancer, chronic inflammatory diseases, atherosclerosis, diabetes, and autoimmune and degenerative diseases.

Neutrophils, which target microorganisms in the body, can also damage host cells and tissues.

Neutrophils are key mediators of the inflammatory response, and program antigen-presenting cells to activate T cells and release localized factors to attract monocytes and dendritic cells.

Macrophages are important components of the mononuclear phagocyte system and are critical in inflammation initiation, maintenance, and resolution.

During inflammation, macrophages present antigens, undergo phagocytosis, and modulate the immune response by producing cytokines and growth factors.

Mast cells, which reside in connective tissue matrices and on epithelial surfaces, are effector cells that initiate inflammatory responses.

Activated mast cells release a variety of inflammatory mediators, including cytokines, chemokines, histamine, proteases, prostaglandins, leukotrienes, and serglycin, proteoglycans.

Multiple groups have demonstrated that platelets impact inflammatory processes, from atherosclerosis to infection.

Platelet interactions with inflammatory cells may mediate pro-inflammatory outcomes.

Source: Chen, Linlin et al. “Inflammatory responses and inflammation-associated diseases in organs.” Oncotarget vol. 9,6 7204-7218. 14 Dec. 2017, doi:10.18632/oncotarget.23208

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 3.0 (CC BY 3.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Diseases associated with inflammation [7] [8] [9] [10] [11] [12] [13] [14]

- Age-related macular degeneration

- Alzheimer’s

- Ankylosing spondylitis

- Arthritis

- Asthma

- Atherosclerosis

- Autoimmune diseases

- Cancer

- Cardiovascular disease

- Chronic inflammatory diseases

- COVID-19

- Degenerative diseases

- Depression

- Diabetes

- Fibromyalgia

- Hypertension

- Inflammatory bowel disease

- Metabolic syndrome

- Obesity

- Osteoporosis

- Parkinson’s

- Periodontitis

- Psoriasis

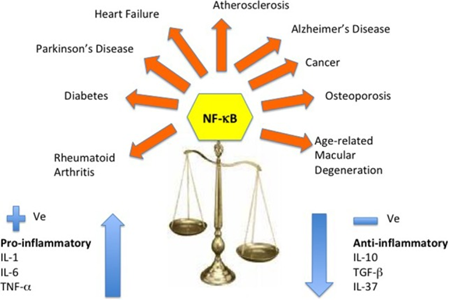

Cytokine dysregulation and NF-κB inflammation pathway. This reshaping of cytokine expression pattern with a progressive tendency toward a pro-inflammatory phenotype has been called “inflamm-aging” and is found associated with age-related diseases. Several molecular pathways have been identified that trigger the inflammasome and stimulate the NF-κB and the IL-1β-mediated inflammatory cascade of cytokines.

Source: Rea, Irene Maeve et al. “Age and Age-Related Diseases: Role of Inflammation Triggers and Cytokines.” Frontiers in immunology vol. 9 586. 9 Apr. 2018

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY).

Inflammation of various tissues predisposes organs to cancer development. For example, inflammatory bowel disease and colon cancer, H-pylori-induced gastritis and gastric cancer, and prostatitis and prostate cancer.[15]

Next Up: Inflammation and aging combine to create “inflammaging.”

References

[1] Chen, Linlin et al. “Inflammatory responses and inflammation-associated diseases in organs.” Oncotarget vol. 9,6 7204-7218. 14 Dec. 2017

[2] Das, Undurti N.. Molecular Basis of Health and Disease. Germany, Springer Netherlands, 2011.

[3] Stone, William L., et al. “Pathology, Inflammation.” StatPearls, StatPearls Publishing, 27 August 2020.

[4] Chen, Linlin et al. “Inflammatory responses and inflammation-associated diseases in organs.” Oncotarget vol. 9,6 7204-7218. 14 Dec. 2017

[5] Mahan, L. Kathleen; Raymond, Janice L. Krause's Food & the Nutrition Care Process - E-Book (Krause's Food & Nutrition Therapy). Elsevier Health Sciences. Kindle Edition.

[6] Qian, Mengjia et al. “Autophagy and inflammation.” Clinical and translational medicine vol. 6,1 (2017): 24.

[7] Chen, Linlin et al. “Inflammatory responses and inflammation-associated diseases in organs.” Oncotarget vol. 9,6 7204-7218. 14 Dec. 2017

[8] Rea, Irene Maeve et al. “Age and Age-Related Diseases: Role of Inflammation Triggers and Cytokines.” Frontiers in immunology vol. 9 586. 9 Apr. 2018

[9] Mudambi, Kiran, and Dorsey Bass. “Vitamin D: a brief overview of its importance and role in inflammatory bowel disease.” Translational gastroenterology and hepatology vol. 3 31. 29 May. 2018

[10] Hunter, Philip. “The inflammation theory of disease. The growing realization that chronic inflammation is crucial in many diseases opens new avenues for treatment.” EMBO reports vol. 13,11 (2012): 968-70.

[11] Franceschi, Claudio, and Judith Campisi. “Chronic inflammation (inflammaging) and its potential contribution to age-associated diseases.” The journals of gerontology. Series A, Biological sciences and medical sciences vol. 69 Suppl 1 (2014): S4-9.

[12] Moeller, Mark et al. “Mortality is associated with inflammation, anemia, specific diseases and treatments, and molecular markers.” PloS one vol. 12,4 e0175909. 19 Apr. 2017

[13] Mahan, L. Kathleen; Raymond, Janice L. Krause's Food & the Nutrition Care Process - E-Book (Krause's Food & Nutrition Therapy). Elsevier Health Sciences. Kindle Edition.

[14] Yazdanpanah, Parviz, et al. "Diagnosis of Coronavirus disease by measuring serum concentrations of IL-6 and blood Ferritin." (2020).

[15] Mueller, Monika, Stefanie Hobiger, and Alois Jungbauer. "Anti-inflammatory activity of extracts from fruits, herbs and spices." Food Chemistry 122 (2010): 987-996